The cry has gone up to name the north-eastern or scoreboard pocket at Adelaide Oval the Eddie Betts Pocket.

And no wonder after the Crows’ electrifying small forward booted his freak, running checkside goal from the pocket against North Melbourne, then followed up with two stunning last-quarter goals from the same area to ice the Crows’ Showdown 37 success against Port Adelaide.

“I think we’ve now got the Eddie Betts Pocket, I think we can officially call it that – even when Port plays here,” Crows coach Brenton Sanderson enthusiastically announced. “He doesn’t miss from there, in front of the scoreboard, in front of the hill.”

Almost half-a-century ago, it could have been named the Peter Endersbee Pocket. Back in 1968 a blond bombshell Sturt rover left a packed Adelaide Oval spellbound, then electrified by two successive checkside goals in grand final glory against Port Adelaide.

When the remodelled Adelaide Oval was being named in honour of SA football and cricket greats there were even a handful of fans who suggested the north-eastern pocket be officially named in tribute to Endersbee.

Fittingly, Endersbee was on hand at Adelaide Oval to see his first game of football at the Oval since the mid 1990s, when Betts emulated his achievement to stun Port. And Crows supporter Endersbee, like so many of the pulsating crowd that afternoon, enjoyed the party.

“I love Eddie,” Endersbee says unashamedly. “I was happy to be there, in the Max Basheer Stand, and I have to admit it occurred to me that was the spot where I kicked those two goals from … it was the identical spot between the pocket and the half-forward flank. It was a long distance for a checkside … 40 metres you know.”

Endersbee, who has lived in Sydney for 16 years, could be excused for feeling more than a pang of nostalgia returning to his old hunting ground in the city. “I was very pleased they kept the scoreboard and the Moreton Bay figs,” he said. “Overall it was dynamite … but mainly because we won.”

Endersbee loved the fact that, despite the remodelling of the iconic ground, fans were still standing under the historic Oval scoreboard, built in 1911 and as majestic as ever.

Endersbee’s mind had wandered back to his life-defining day of 1968 earlier this year when he was presented with a picture of him and his Doubles Blue team-mates charging out for the grand final, chasing a hat-trick of premierships and third successive win against Port in the one that matters.

Taken by Sturt enthusiast Bill Ferme, who also captured a remarkable image of the Beatles driving up Anzac Highway on their famous visit to Adelaide a half-century ago, Paul McCartney, John Lennon and George Harrison giving the thumbs-up, it is an extremely rare colour image of football and Adelaide Oval of the era.

There was excitement in Endersbee’s voice as he named every Sturt player in the photo: “That’s Bob Shearman out in front, leading the way as usual, then John Murphy with the ball, Roger Rigney, Bruce Jarrett, Tony “Doc” Clarkson, Malcolm Hill – the Enforcer – me, my old mate Rick Schoff, I think that’s Daryl Hicks, then the late and great Brenton Miels, a mate of mine …” The names rolled off the tongue, myriad memories coming to mind, a champion team of champions. No wonder they won five straight.

Fittingly, the taller-than-usual rover-small forward, wearing the No. 29 guernsey, was positioned right in front of the goals he was so soon to split with those checkside punts.

The scoreboard, crowd and Moreton Bay fig trees didn’t look that much different than they do today. But the fans sure were packed in the outer and on the eastern wing was the temporary stand that was erected for finals in an era regarded fondly as the greatest in the SANFL’s long and wondrous history.

The crowd for the 1968 grand final was even bigger than at the bigger-than-big Showdown. There were 57,811 back in ’68 and 50,552 at Showdown 37, so don’t for a moment think football wasn’t huge in the city of churches before the AFL rolled into town.

In Endersbee’s days – they weren’t long enough, he played just 47 games between 1967-71 but with three premierships – more people were standing than sitting, of course. And at the mighty Sturt-Port clashes of the mid-to-late 1960s, crowd support was split right down the middle. The three biggest crowds in SA football history witnessed epic Sturt-Port grand finals of the sixties and ’70s. They were left spellbound by the new-style skill-based football 10-time premiership coach Jack Oatey introduced – Endersbee called it the “handball revolution”. It propelled Sturt to be the unquestioned power of SA football, usurping Port Adelaide after the Magpies had claimed nine premierships in 12 years, winning seven in a decade of their own.

In 1965, the revolution had begun. In an epic grand final at Adelaide Oval the then record crowd of 62,543 saw Sturt fire out 52 handballs. Port Adelaide had 10 – yes, 10, for the whole game. The Magpies held on from the fast-finishing Double Blues to win by just three points with three last-gasp shots at goal failing to snatch victory for Oatey’s talented men. By the following season they had doubled Port’s score in the grand final – 16.16 to 8.8 – and footy had changed forever, a run-on game where handball – previously only used when you were in desperate trouble – was being unleashed as an attacking tool.

This signal for the changing of the times came four years before Carlton coach Ron Barassi's legendary half-time grand final edict to "handball, handball, handball" when the Blues were in dire straits against Collingwood. Carlton completed the most famous comeback victory of all time and handball was suddenly being looked at in a different way across the border.

By 1968 the checkside punt that Oatey had routinely drilled all his players in at training was another new, lethal weapon. When Endersbee slotted his two early goals in the ’68 premiership decider, Oatey deservedly was delighted, barely able to conceal his excitement as he turned to chairman of selectors Clayton “Candles” Thompson on the bench on Adelaide Oval’s boundary line, declaring Port “won’t know what he has done”.

Some commentators still get confused by the checkside kick. But back then it was all a complete mystery – “people thought it was magic,” Endersbee said. The narrator for the official film of the 1968 grand final said of the Blues’ breathtaking opening, “Endersbee screw punts Sturt’s first goal”. When he describes the second checkside goal, soon after, he seems to sense there is something special about what the Blues tyro is doing – even though this is a carbon copy of the first goal.

“He’s about thirty yards out - almost identical to the position from where Endersbee kicked an earlier goal. Another ‘backscrew punt’ and another goal - his second and Sturt's third.”

Sturt won the grand final by 27 points – and Endersbee kicked 4.3 (yes, that’s 27 points).

Endersbee saw – and celebrated – on television what was described as Betts’ “wonder checkside kick” in round 13 against North Melbourne on the run from the same pocket. But Endersbee laments very few top-level players can kick “the classical checkside”. That means kicking it as a set shot, without running around to improve the angle. “And I’m not a fan of standing side-on to the goals, facing the oval. Why not just face them and kick the classical checkside kick?” he muses.

While Geelong’s Steve Johnson may not face the goals when he shoots from an “impossible” angle, Endersbee says he neither kicked to, nor even thought about the goals – and that was under instructions from Oatey. “You have to kick it to the crowd,” he says of what Oatey taught. “People think it was magic … maybe … but it’s about forgetting the goals … kick the kick and the rest will follow.”

It’s mind over matter, according to Endersbee. “Anyone can cut a ball (with their foot to kick the checkside). The problem is here,” he says tapping his head, saying most players miss their kicks to the near side because “they can’t forget the goal”.

“I am proud of those two (kicks in the grand final) because they are classic checksides (from set shots),” he says.

But, perhaps surprisingly, it is Endersbee’s first kick in league football which is his favourite. It also was on Adelaide Oval, it also was a checkside punt, this time from the south-western pocket, and it also was in 1968. With Oatey, it was always about the “skill factor”, that was what would prove the difference, win you matches, when it came to the crunch. So it is hardly surprising Oatey whooped in delight from the bench as Endersbee booted his miracle goal in the wet in the opening minute of the round five game against South Adelaide. Endersbee’s father, in the John Creswell Stand at the southern end, tossed his hat high in the air in celebration. “I take it that’s your son,” an amused spectator said to him.

“That kick’s my greatest memory in football,” Endersbee says, “even better than the two goals in the 1968 grand final.”

It’s not surprising Endersbee felt right at home watching Betts’ heroics at the Oval, despite nearly two decades having whizzed past since he was last there.

Endersbee, who never warmed to Football Park, believes the new-look Adelaide Oval is “helping build up the status of SA football”.

This was something Endersbee had done at the Oval back in ’68, when, in a Champions of Australia clash between SANFL and VFL premiers, Sturt tackled Carlton.

After the game, in which the VFL Blues proved too powerful, Carlton boss Barassi wrote in The Age: “Peter Endersbee is most impressive for a first year player. His height will always present a big problem to back pocket players.”

At 180cm Endersbee was taller than almost all rover-small forwards of the day and when you added electrifying pace and sublime skills to the equation it was hardly surprising he created quite an impression in this end-of-season clash. Legendary Big Nick, Carlton skipper, ruck great and future premiership captain-coach John Nicholls, like Barassi, was impressed. He planted his big paw on Endersbee’s back in the players’ race after the clash, booming: “Good game, laddie.” Endersbee had been “desperate to beat the Vics”, rather than cross the border and play in the VFL (such a move was almost impossible back then), although there was not surprisingly a strong rumour Carlton wanted to talk to him. He would undoubtedly have been a sensation.

However, Endersbee’s place in history had already been assured in SA, the birthplace of the checkside punt, with those two kicks. “Kicking two in a row proves it wasn’t a fluke,” he says.

While Endersbee could perform miracles from the boundary line, in the years of make-love-not-war and flower power of the late 1960s, early ’70s, he also pushed the boundaries off the field.

He even had the audacity to grow his hair long.

It’s hard to believe such a simple act could spark a controversial saga but staid, respectable Adelaide of the 1970s wasn’t ready for blokes with long hair. And Oatey certainly wasn’t.

As Sturt set its sights on a fifth successive premiership at the start of pre-season training in 1970, Endersbee “rolled up with a summer's worth of bleached long blond locks, with a beard to boot”. After training he was presented with an ultimatum conveyed by the club secretary: “Cut your hair or don't train.” He chose the latter.

By the next morning Endersbee’s plight was made public in The Advertiser. The star rover sensationally was officially banned from training for having “unacceptably” long hair.

Endersbee recalled: “I knew the hair directive had come from the coach even if it had been packaged as if it were club policy. It was his policy more like it, and therefore the club's. Eventually, Jack asked me to come and pay him a visit at his eastern suburbs home.”

Oatey, whose philosophies on sport and life remain with Endersbee today – he takes them out onto the tennis court with him every time he plays – made himself comfortable in the front seat of his rebellious young star’s FJ Holden. “I really don't see what hair length has to do with my ability to play. Therefore it should have no effect on the club,” Endersbee said, standing his ground.

But Oatey, as always, was well prepared. “What if some player grabbed you by the hair and broke your neck?” he asked. “If I'd let you play I'd have it on my conscience for the rest of my life.”

After some to-ing and fro-ing, Endersbee claiming it was his decision and therefore his responsibility and Oatey retaliating with, “even if there's the remotest likelihood of it happening, I'd take it with me to the grave”, Endersbee fired back with, “In three weeks' time I'll be eligible to die for my country, when we're not even at war. No-one seems too concerned about that. So don't worry about my ability to fight my own battles out on the footy field”.

Oatey opened the door to get out, turned for a brief second to look Endersbee squarely in the eye, and said: “You can keep the hair. Get the beard off. See you Thursday. You'll be in the team.”

And within a couple of years, almost everyone in the SANFL had long hair. Some players even had beards!

Endersbee shone out in the Blues’ 1970 grand final win, picking up 30 kicks in the rain to be rated among the best three afield, then early in the following year, having “turned hippie”, was gone, heading for northern New South Wales.

Although Endersbee missed his chance to play for Carlton, he lived there from 1977 into the nineties. To be a true-blue supporter of a football club you have to go through the bad times as well as the good. So Endersbee certainly qualifies as a Crows fan – he was there in the rain and cold as Adelaide copped pummellings at Windy Hill, Victoria Park and Kardinia Park, “Big V” crowds and power teams doing their darndest to give the SA “novices” a very warm welcome to the big league.

On radio, at least, he returned to the city of churches in the guise of Professor Jack Revere, masquerading on the airwaves as “the intellectual member of the Crows’ Think Tank”, a label coined by well-known SA media identity – and Crows and Sturt fan – Keith Conlon.

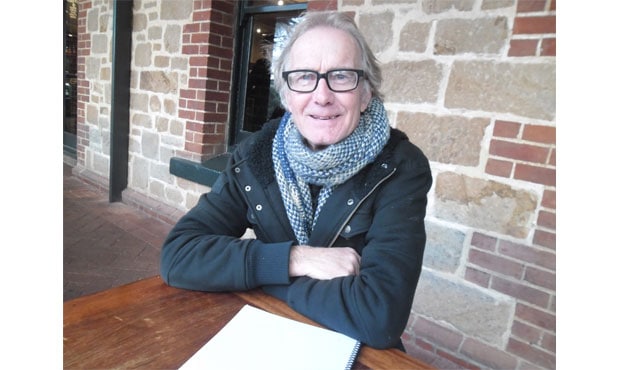

Endersbee lived briefly in a caravan in New Zealand before the Crows reaching a grand final for the first time enticed him back to Australia. For the past 16 years he has lived in Sydney, working as a commercial photographer. He has been a semi-professional musician on and off since 1976 and also a teacher but his great passion is for writing. Endersbee has met with success in this field too, claiming second prize in the Tom Howard Short Story Award in 2004 and winning the Varuna Fellowship in 2012.

If you reckon Endersbee’s life has the makings of a great book, you’re right on the money. He had previously written two memoirs on his football career and life as a “hippie”. The first, The Other Man's Grass, was penned in that Kiwi caravan. It was an attempt to answer the question so often asked of him: “Why did you leave the game?" This is an absorbing tale that weaves between Unley Oval, Flinders University, the streets of the Moratorium marches against the Vietnam War in 1969-70 and the family home in Lower Mitcham.

But nothing will match the raw emotion of his tell-all journal of his experience with prostate cancer. The soon-to-be published book reveals plenty about the insidious disease that men just don’t want to talk about and all-too-often is swept under the carpet. The book, written in a moving and sometimes explosive manner, is Endersbee’s warts-and-all story. Just as they did at Adelaide Oval back in ’68, people will stand up and take notice.

Here’s hoping, like those two kicks of his did, it might change things for the better.

NEXT: From reverse screw punt to checkside